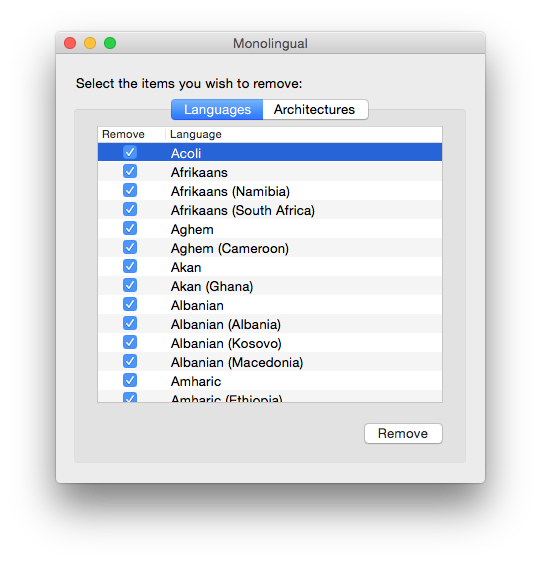

“When competition occurred between two languages, bilinguals recruited additional frontal control and subcortical regions, specifically the right middle frontal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus, caudate, and putamen, compared to competition that occurred within a single language.” Marian explains, “that the size and type of the neural network that bilinguals recruited to resolve phonological competition differed depending on the source of competition.” The study results show that different areas of the brain are needed to cope with phonological competition from within the same language, compared with between-language competition. In monolingual people, areas in the frontal and temporal language regions – more specifically, the left supramarginal gyrus and the left inferior frontal gyrus – are activated when faced with phonological competition. In monolinguals, this “phonological” competition occurs only between words from the same language.īut bilinguals have similar-sounding words from their second language added into the mix. Marian also sought to clarify which brain regions are involved when bilinguals are faced with words that sound similar. Scientists think that the brains of bilinguals adapt to this constant coactivation of two languages and are therefore different to the brains of monolinguals. In fact, when a bilingual person hears words in one language, the other language also becomes activated.

Marian explains in the paper that “ilinguals’ ability to seamlessly switch between two distinct communication systems masks the considerable control exerted at the neural level.” The research involved 16 bilingual individuals who had been exposed to Spanish from birth and to English by the time they were 8 years old. Viorica Marian – a professor of communication sciences and disorders at Northwestern University in Evanston, IL – and colleagues published a study last month in the journal Scientific Reports, investigating which areas of the brain are involved in language control. Scientists are now starting to unravel the mysteries of the bilingual brain and shed light on the advantages that having this skill may bring. While there is a tendency on the whole for bilinguals to lag behind monolinguals in their language development, this isn’t true for all children. Mixing languages does not seem to hold bilingual children back from learning both languages, but it takes longer to learn two languages than to learn one. Interestingly, children seem to naturally develop an understanding of who in the house speaks which language early on, and they will often choose the correct language to communicate with a particular individual – a phenomenon I have witnessed with my daughter, who is exposed to both German and English. When bilinguals mix words from different languages in one sentence – which is known as code-switching – it is not because they cannot tell which word belongs to which language. They are also capable of developing vocabulary in two languages without becoming confused.

Do the brains of bilinguals differ from those of monolinguals? And do bilinguals have the edge over monolinguals when it comes to cognitive functioning and learning new languages?Īs a member of a bilingual household, I was keen to investigate.Ī 2015 review in the journal Seminars in Speech and Language explains how bilingual children develop their language skills, dispelling commonly believed myths.Īccording to authors Erika Hoff, a professor of psychology at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, and Cynthia Core, an associate professor of speech, language and hearing science at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C., newborns can distinguish between different languages. With a rising number of bilingual people comes increased research into the science that underpins this skill. This number has more than doubled since 1980, when it stood at 9.6 percent. Data from the United States Census Bureau show that between 20, around 20.7 percent of people over the age of 5 spoke a language other than English at home.

Instead, the number of bilinguals has been rising steadily. Gone are the days when using a second language in the home was frowned upon, labeled as confusing for children and supposedly holding back their development. How does the brain cope?Īttitudes toward bilingualism have changed significantly in the past 50 years. Share on Pinterest Both languages that a bilingual person knows are switched on, even when communicating in only one of them.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)